KEANE TO BE BEST

by R.J. DOYLE

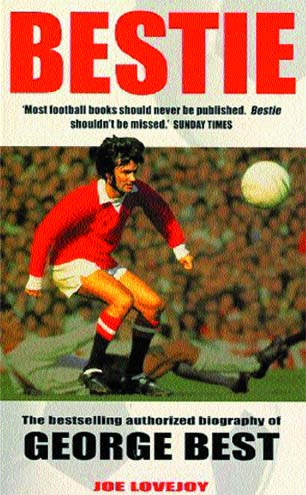

I was going to write about Nicolas Sarkozy, but something far more important has come up, beautifully booting the French establishment’s Incrediboy off the page. The great George Best, a true “Incredible”, has finally left us, as Eric Cantona put it, to weave his soccer magic in heaven. Best’s premature though not unexpected death at 59 has saddened millions of sporting fans around the world, including in France. It is the final episode in a tragicomedy which has unfolded over 40 years. This was George Best, the “fifth Beatle”, the 60s playboy with that Paris Match touch of celebrity which the French admire. No movie will ever match it, though Robert de Niro’s Raging Bull comes close.

I was going to write about Nicolas Sarkozy, but something far more important has come up, beautifully booting the French establishment’s Incrediboy off the page. The great George Best, a true “Incredible”, has finally left us, as Eric Cantona put it, to weave his soccer magic in heaven. Best’s premature though not unexpected death at 59 has saddened millions of sporting fans around the world, including in France. It is the final episode in a tragicomedy which has unfolded over 40 years. This was George Best, the “fifth Beatle”, the 60s playboy with that Paris Match touch of celebrity which the French admire. No movie will ever match it, though Robert de Niro’s Raging Bull comes close. Sport does not always steal the front page headlines for so long this way, but Best was everyone’s brother, son and hero. Coincidentally, the Belfast boy’s passing stole the limelight away from another hero, another Irishman and another son of Manchester United: Roy Keane. George and Roy share much in common, beyond the fact that both made immeasurable contributions to Britain’s largest club only for that relationship to end suddenly and controversially, in Roy’s case, just recently. Both men sought perfection.

With the media hype receding, how great was Best really? Such debates are endless. Danny Blanchflower, former Spurs and Northern Ireland boss compared Best to other stars of the time: "His movements are quicker, lighter, more balletic. He offers the greater surprise to the mind and eye, he has the more refined, unexpected range. And with it all there is his utter disregard of physical danger. He has ice in his veins, warmth in his heart and timing and balance in his feet." Just read the report in The Guardian from the 1968 European cup victory (sports section at www.guardianunlimited.co.uk) to grasp just how huge the young Best really was.

But there is more than skill in this saga. You see, people may compare Best to Maradona and Pele, but would those two have generated such an outpouring? Maybe I am a sentimentalist, but on hearing of Best’s death on 25 November, I emailed family and friends at the time: “I for one am very sad. Like a rib gone, a shoulder, a bone of my youth, a reason, why we are here...” Make me cringe a little -- I am not even a ManUnited fan! But that is how I felt.

One journalist suggested such outpouring is a generational thing, lost on today’s 20-year-olds. He misses the point: tragic figures hold timeless lessons for everyone. Best’s dying is our dying too. Like Pele and Maradona, Best was football, but he was more than that. As Joyce rewrote English, Best recast sport. His private life which obsesses some journalists was in fact a scene in our human tragedy, everyone’s search for perfection. As former England star Jimmy Greeves put it, Best drank to fill the emptiness of not playing! It is not enough to be great at your sport or at your job. As I wrote in that email, Best embodied “creativity, joy, human failure, kindness, loneliness, beauty, tragedy, all the expressions that make up a personality, the imperfection and perfection of life all wrapped up in one person.” At the same time, life is simple, and “kids will always dream of playing like Georgie Best...”.

Best’s tragedy is also that of Roy Keane, who is still very much alive, of course. But rather than a fairly wild (and lonely) “public” life, Keane has been driven into another kind of isolation. His quest for perfection wells into anger and frustration at the imperfection of his colleagues, and perhaps the shortness of life itself. Both Best and Keane, hugely talented, filled with creativity and genius, suffered from this fatal flaw.

As well as skills, George Best was a fighter, but perhaps Roy Keane was more of a leader. He also had underrated skills, without which his “fighting spirit” would be but a roar. I still think Keane’s headed goal against Juventus in the semi-final of the European Champions League in 1999 was one of the most inspiring goals ever: the angle, the power, the determination, the moment, the opposition and the outcome. It rallied Man United to go on to win the trophy (see www.uefa.com/video/archive/). Roy sat out the final on the bench, having picked up two yellow cards against Juventus. He missed the final combat, just as Best never made the World Cup. Man United was simply the worthy stage for this Shakespearian tragedy.

© Copyright Irish Eyes - Photos: © The Irish Club - www.irisheyes.fr - contact